It became my job to define Risberg, to find out why a player of this caliber would do what he did. I also had to give myself reason to fulfill the promise of the play, so every time I walked onstage as Risberg, not only did I have to know why I wanted to throw the World Series of 1919, but so did the audience. The first cast reading was May 5. I had until May 19, first rehearsal.

It has always been my contention that each person has a core to him, a motivation that propels him through life. As an actor, if I can find that core, I give myself something to play.

I began to read the history of the times immediately pre- and post-scandal. I started with Volume II of David Quentin Voight's ''American Baseball.'' Voight dealt with the economic situation of the country, the depression of 1917-18. The shortened seasons of 1918-19 as a result of United States involvement in World War I caused the players' salaries to be cut. Over all, what struck me was the fact that baseball is a direct reflection of our country. When news of the scandal broke in 1920, there was a fear in this country of Bolsheviks infiltrating our society. Writers in The Sporting News referred to gamblers as undercurrents of society undermining the American game, much the same as cocaine dealers now seem to be a major threat. Remember, the eight White Sox players implicated, were never indicted although Commissioner Kenesaw Landis banned all from the sport for life.

The more I read, the less I found about Risberg. In the play, the character of Risberg insists, ''I never talked.'' The man didn't either. I needed more history. I read Eliot Asinof's ''Eight Men Out.'' Asinof's book is a chronicle of the 1919 scandal, but the work was more event-filled than personality-aware. I had to start building my own theories about Risberg.

I met with Lawrence Ritter, author of ''The Glory of Their Times,'' and he gave me a tape of interviews with old-timers who played between the late 1800's and early 1920's. Chief Meyers, Rube Marquard, Fred Snodgrass and others spoke of their rise and of a simpler America. In fact, when the rest of the cast listened to the tape, it helped us accept who we were and not become overly dramatic. These old-timers were discriminated against because they were ballplayers. They spoke of their lives and the tough times as if it were no big deal.

My girlfriend is a Swede, and she went to the Church of Sweden on 48th Street and traced the name Risberg. It's an uncommon name, and the Risbergs who came to this country were either theologians or teachers.

The name ''Charles August'' is an Americanization of the Swedish ''Carl August,'' a popular name in Sweden in the late 1800's. This gave credence to my speculation that Risberg was first generation, born in this country but maintaining an immigrant mentality.

The facts about Charles August (Swede) Risberg were that he was tough, had a good glove, moved well to his left, had a great arm and was an adequate hitter. He was born in San Francisco in 1894, played in the California League before joining the White Sox in 1917, the year the Sox won the World Series. In all accounts the one thing that always stuck in my mind was that Risberg never spoke about the 1919 scandal. That was a key trait.

From the Hall of Fame, the reaction was warm, but the information scant. That Risberg was involved in the fix might be ascertained from his batting average during the Series, .080.

Also, the story was that when Risberg was at short, he would slow his throw to second so Eddie Collins, an honest White Sox player, couldn't make the throw on to first for a double play. Also, Risberg had played in the California League, notorious for corruption, according to Betsy Tunis, who wrote her masters thesis on baseball corruption at the University of Massachusetts.

It seems the money Risberg was to receive from fixing games was the best he would ever make - reportedly between $3,000 and $10,000. The White Sox owner, Charles Comiskey, was paying him $2,500 in 1919. Risberg was caught up in the American capitalist dream, i.e., success is reflected through money. This was the character trait I focused on, the drive to make money.

I'd found the core, my ''through'' line. I now had to justify my motivation; I had to make the bad good, at least in Risberg's mind. Risberg was used to making money, he'd been on a championship team in 1917 and found his pay cut the next year. Maybe most important, there were other players who were said to be fixing games. But to throw the World Series, perhaps the biggest scandal of all and a sure way to make money, could not be overlooked. Not only were Risberg's peers on other teams corrupt, according to Ms. Toonis's research, but here was his chance to make the big money, the opportunity to outdo them all.

In the drive to make money, a chance to make the ultimate business killing cannot be passed up. In many ways I had made the bad virtuous, but also through acceptance by my historical peers, I'd made the good stupid.

Baseball is a game of skill and those basic skills have hardly changed since its inception. If I could pick up the basic skills of a shortstop, it would key me more into Risberg's character. Since athletes express themselves through their bodies, to adopt the skill of an athlete I would be portraying would lead me more into the physical rhythms of the character.

In the Encyclopedia of Baseball, Risberg is listed as being 6 feet, 175 pounds, batted right and threw right. I'm 6-4, 205 pounds and a natural righty. I knew Risberg had a strong arm, which I don't, but since I wouldn't be throwing on stage, I just had to look like I could throw. In the four years he was in the league, Risberg had 52 stolen bases, which meant he could run. That was our common physical attribute. I started putting in three to five miles a day, which took off some weight and gave me the lean look I'd seen in Risberg's pictures.

Although I'd started to look the role physically, I still didn't feel like a shortstop.

I met with Bud Harrelson, former shortstop and now a coach with the Mets. Harrelson told me he knew a player was ''off'' at short when his rhythm was ''off.'' I made throwing motions, Harrelson corrected me, and we both came up with the ''whippiness'' of a great arm.

We worked on stance. ''It's not a lateral movement,'' Harrelson said. ''It's a turn of the hips, a sprint, then squaring off to the ball.'' He demonstrated, I imitated, he corrected me and we did it again. It became a sort of dance through the Met locker room until somebody looked up and said: ''What's going on here?''

Harrelson left me with a shortstop exercise: Placing two socks 15 feet apart, standing square to one, turning, sprinting to the other, and squaring off to pick it up, just like fielding hot grounders. Then you go the other way, left to right, right to left. When I tacked this exercise onto my workout, it affected my walk because it worked on different muscles in my legs. I began to feel like a shortstop because my legs must've ached like one.

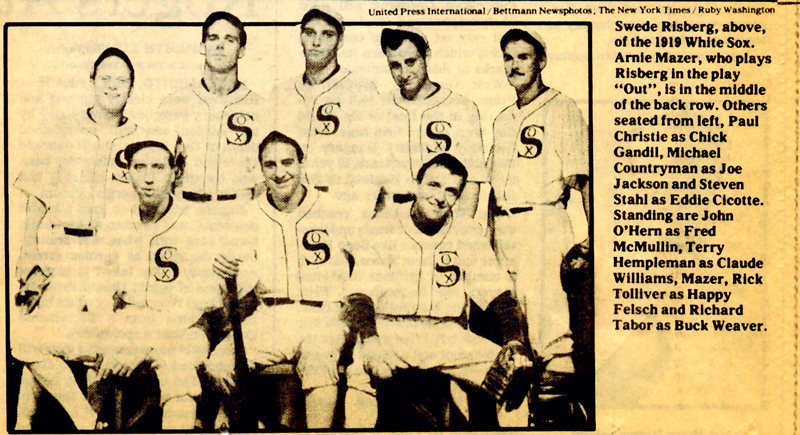

Combining the life history of Risberg I'd researched and conjectured with the exercises I practiced helped me to complete the character and fulfill the script. When I walked into our onstage locker room and mingled with Claude Williams (Terry Hempleman), Happy Felsch (Rick Tolliver), Fred McMullin (John O'Hern), Eddie Cicotte (Steven Stahl) and Buck Weaver (Richard Tabor), it was now done as if we were a ball club. We all approached the roles as ballplayers, each researched in his own way to make the Black Sox alive, on stage.

|